Sleaze Nation: a history

The following piece by Jack Mills was first published in Wonderland magazine.

20 years ago this year, Sleaze Nation, one of the world’s snottiest, most influential style bibles, was born. Speaking to the rebelheads behind this maniacal monthly, we ask: where can magazine publishing possibly go from here?

The mid 90s was a good time for a Great British scandal. Tory MP Shirley Porter was charged with “improper gerrymandering” after conning the taxpayer out of tens of millions, Hugh Grant was caught floppier than usual with LA working girl Divine Brown and Robbie Williams’ teeth were falling out because of an experimental lollipop diet he was trying out. Our celebs and politicians were doing the dirty, and we were laughing about it to each other in our Vauxhall Minis. While The Sun enjoyed a record sales spike in 1996, like a seal of disapproval slapped across the tabloids, one word seemed to define the political climate: “SLEAZE”.

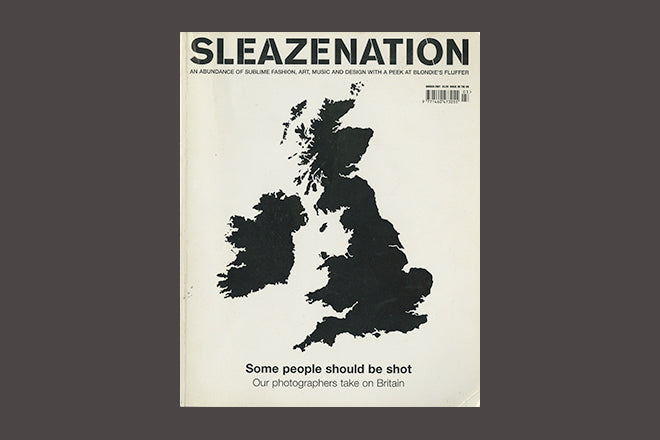

That same year, a style and club culture monthly launched that sent thunderclaps through the magazine industry. Pilfering its name from the tabloid buzzword of the moment and pitching itself as The Face’s toothless, STD-riddled cousin, Sleaze Nation nestled itself in the sweaty folds of Britain’s underbelly and refused to surface until it had a story. It was there, skipping to the front of the club queue, documenting UK youth culture at its vilest. Founded as a free London club listings guide, it went on to enjoy an eight year reign as the world’s most anarchic, unpredictable fashion title, as likely to run a six-page feature on gout as it was a Gucci gatefold.

All you ever needed to know about the magazine appeared as a tiny disclaimer on the masthead of Issue One, Volume Two – the first edition of Sleaze Nation marked with a cover price: “This magazine is not The Economist,” it declared. “It covers its subject matter in a tone in accordance to the subject itself, i.e. not very seriously. The views expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the senior editorial staff, whose views are often far more extreme.”

Features ranged from the insane, to the pointless, to the unimaginably offensive. An article on “The Straight Blokes Who Look Like Gays When They’re Out Clubbing” mocked the Real Life reporting of Hello magazine. Typical front-of-book tidbits included an anonymous confessional from someone who used to bully Ed from The Chemical Brothers, a report on “Kooky Turkish artist” Pinar Yocalan who stuffs cauliflowers with human hair and a DPS on Security Guard street style. One lengthier piece pitted DJ Shadow’s side project U.N.K.L.E against terrible TV spy series, The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

Devilish literary ingenuity was found in the clubbing pages, too. With many entries missing key details (“INFO: FIND OUT FOR YOURSELF”) and names of streets and clubs crude-ified (Notting Hill Arts Club became “NOTTING HILL ARSE CLUB” and Shaftesbury Avenue, “SHAFTME AVENUE”) you get the feeling that Sleaze’s listings pages quickly became an excuse to insult London’s Nathan Barley-esque yute mob. “Jesus, Dickmeister Doris is now doing Sundays at the Dog Star” reads one Brixton entry. “I’m sorry, but I find it increasingly difficult to take a man who wears scary technicolour Goa bastard outfits that seriously at all.” “Lunatic Trash crew dance like punks with a vibrator made by Miss Kitten rammed up their jacksies,” describes one of The End’s much-missed indie nights. Sometimes, it’s fun to just thumb through the dozens and dozens of DJs that have been buried in the sands of time (or NME Radar Tour glitter): Blind Ollie, Wolf Boy Matt, Keiron Accelarator, Capris Injection.

Between op-eds on the merits of shagging your trainers and 12 page photo-journeys into the heart of the British farmyard, Sleaze Nation was capable of brilliant journalism. “True Niggaz Ain’t Gay” explored the rampant homophobia in hip-hop’s biggest circles. Elsewhere, “Zi Hackadamy” was an expose on the world’s first internet hacking school, whilst “The Mercury 13” told the little-known story of a privately-funded, female-only space mission.

Often, fashion editorials were all-out assaults on tabloid storytelling and Western consumerism. In one, models are captured dilly-dallying about on a distant yacht, mimicking the grainy voyeurism of celebrity photography. A redtop-esque caption reads: “SO IN LOVE… Paul grabs a sly kiss on the terrace. Just look at the detail – you can even smell her Huit bathing suit beneath that Miu Miu shirt, and retch over the couple’s matching Antik Batik sarongs.” Another story follows a day in the life of six south London shoplifters – hired actors of course, blinged out in Versace and Burberry.

And the stuff that didn’t make the cut? Responding to a letter of complaint about a fashion submission, Sleaze Nation’s then-editor Neil Boorman printed: “Unfortunately, all our shoots for the next few issues are done. We forwarded everything to Dazed as a courtesy, so they might be in touch.”

The Story. Genital Warts ‘N’ All.

Sleaze Nation was founded by Adam Dewhurst and Jon Swinstead in a central London pub. It was early 1996, and Dewhurst, then a Royal Holloway postgrad, was approached by the owner of a Wiz-esque satirical adult comic. “He said that if I ever had a cool idea for a magazine, we should give him a call. Then, out he staggered into the night.” The pair declared war on the pompous publishing horse, promising to start a magazine to run his to the ground the following morning. “We both passionately felt that existing magazines on the newsstands trying to appeal to us at that time didn’t connect,” Dewhurst says. “They were dumbed-down editorially, treated the reader as a fool, were led by press releases and advertising spend and took it all too seriously.” Soon, the pair were researching print houses, publishing costs and office space.

They needed an Editor too. Fellow nightlife extremist and Royal Holloway expat Steve Beale, who worked at a Camden club listings guide called The Lock, was approached by Swinstead and Dewhurst about launching a London-wide equivalent. At the time, Beale lived on one of The Lock-owner’s sofas. For extra Foster’s dosh, he wrote a club column for Royal Holloway’s student rag under the guise of a pair of flouncy socialites called Deborah Diamond and Cassie Fox-Trotter. “I was suitably vile about the Destroy-wearing types who went to Ministry of Sound,” Beale tells me in the Hoxton bar I meet him in.

Soon, alongside Art Director Steve Lazarides, Tristan Dellaway, Martin Tickner (who is now a staffer at Love magazine) and the publishing duo, the magazine set up shop in a cramped space just off York Way, north London. Beale, at the time an avid follower of The Sun and notorious Leeds club promoter Dave Beer’s “Back2Basics” rave flyers, coined the magazine’s title.

Documenting everything from India’s spiralling Psytrance scene to promoter Cymon Eckel’s new fashion industry hangout Riki Tik, one of Beale’s early-days columns was called “Vile Clubbing”- a look at the city’s more unsavoury after hours options. Needless to say, it had long beaten Vice’s identical series, Big Night Out, to the mark. “I remember

“It was really a drugs magazine,” reasons Beale of Sleaze Nation’s first year. “In the sense that it was fuel for conversations you might have when you were off your head. I remember an early feature called ‘Can You Get a Horse Into a Club?’”

Rather than waste stocks outsourcing distribution, Sleaze’s publishers went pirate, renting a barely-legal van and dropping copies off in London’s tastemaking nightspots: Hoxton Square’s The Blue Note (home to Goldie’s legendary Metalheadz night); Turnmills and the 333. With clubbing stalwarts Bagley’s and The Cross round the corner from the Sleaze office, and The Egg directly opposite, they were in good company. Even in year one, the team were giving away 20,000 copies a month without breaking sweat.

An early issue launch party at Brick Lane’s Old Truman Brewery turned into a full-on riot, with punters smashing through windows and running around like hare-brained, semi-naked zombies. “The owner said he felt like the place had been raped,” remembers Beale, who refused Martine McCutcheon entry because “she would have been the only celebrity there.”

Come 1997, the magazine was available in 30 different countries and was being filed alongside i-D and The Face as serious gamers in the fashion industry (it helped, of course, that Beale regularly sent young writers to intern at the Dazed offices to pinch ideas off their flatplan). Even David Bowie wanted in on the action, ringing up the York Way office one rainy afternoon. “I think he just wanted some attention, he was pretty naff around that time,” the editor says. “I said to the work experience person: ‘Did you take a number?’ and they went, ‘Nah.’” Other celebs weren’t so keen on the Sleaze schtick, though: in a 1999 issue of EMAP film magazine Neon, Vincent Gallo threatened to track down and murder the then 25 year-old Beale.

“We had a tractor on the fucking cover with Sleaze Nation written on it, and WHSmith used to put us with the farm magazines,” Beale chortles. Regardless, big-name corps like Levi’s and Coca-Cola were contacting him for ad space, not the other way around. It meant that Beale and co. could assert creative control over brand partnerships: often, they refused to sign a deal if they weren’t allowed to produce the campaign themselves.

Increasingly, Sleaze seemed to attract the type of creative who was willing to gamble their career on a vision – the fashion scene’s feather rustlers. “We really didn’t know what the fuck we were doing, and I mean that in a bad way,” Beale says, grinning at my KLF t-shirt. “But Jo-Ann Furniss (who would later became editor-in-chief at Arena Homme +) was very important early on as far as the tone went. She knew what clubs to go to, what fashion to wear and how to be funny.”

The magazine wasn’t just a platform for London’s wayward-leaning writing talent: the visceral reportage work of original Sleaze recruits Jason Manning and Ewen Spencer has had a long-term impact on fashion photography. “It was unlike anything else I’d seen at the time,” says Sleaze Features Editor Justin Quirk, now a long-form writer at The Sunday Times. “The black and white club photography they ran at the back of each issue was this really bleak, funny counterpoint to the sort of thing you saw in Ministry or Mixmag… You see a lot of it nowadays. The stuff in Sleaze Nation was more like war-zone photography.

“There was also this fascination with really mundane British suburban life,” Quirk continues. “Things like awful nightclubs in Streatham with free buffets, weird Home Counties weddings, that quite heavy side of gay nightlife that you never really saw written about elsewhere. Steve’s ability to spot people who were going to be really major talents was incredible.”

After graduating from art school in Brighton, Spencer got straight on the phone to Sleaze Nation. Beale ask him to come in after seeing a collection of postcards Spencer had shot — a vérité-style photoessay on Northern Soul clubbers. “Steve Lazarides had a policy of rejecting ‘known’ photographers and choosing new people that he thought worthy of the irreverent attitude the magazine had,” Spencer explains. Handing the photographer a roll of film and sending him out into the black, Spencer explored the wonkier end of London’s midnight gatherings. “The Beautiful Octopus Club

In 1999, Beale was offered a title at The Face. Editor Ashley Heath had charged the pair, along with five others – dubbed “The Magnificent Seven” – with reinvigorating the magazine’s declining sales figures. Stuart Turnbull, a regular fixture on the masthead, soon took charge.

Before Sleaze Nation, Turnbull was a club promoter, running nights like Fine and Dandy - a techno-meets-rock’n’roll monthly in an old man’s boozer. He stood in for a couple of issues while the tremors of Beale’s departure ebbed out, before becoming Editor-proper later that year. I meet Turnbull in The Fox, a Shoreditch pub beneath the magazine’s HQ after York Way bit the dust. A place of anarchy and assembly for the team 15 years ago, where divvy nu-ravers once table-hopped to Selfish Cunt tunes, sad menus now sit.

Turnbull’s premise for the mag was pretty simple: write about what you know. Even if what you know is the history of Angel Delight. “‘Cool’; no-one used that word in that office,” he says. “It was out of bounds. We weren’t being ironic when we wrote about darts. It was in the magazine because we liked watching darts, you know?”

Like Beale, Turnbull wasn’t going to sit around reading grey-sludge press releases for issue inspo. In the early 2000s, the streets of east heaved with memorable characters: locals worth telling the world about. “‘Things have really changed around here,’” he recalls an elderly woman called Rita telling him in a nearby sweet shop. “She said, ‘I remember when people were walking round here with their faces on fire. And I was like: ‘For fuck’s sake…’” Referring to Blitz-era London, lovely Rita prompted a story in the following issue of Sleaze about gift packs that Harrods sold to WW1 soldiers, stuffed with Class A drugs.

Kitchen-sink realism was rarely the order of the day under Turnbull’s reign, though. Lies were allowed too. Vice may have just published “The Hype List” - an index of made-up creatives currently shaping the zeitgeist - but Sleaze were pulling this shit back in the Willennium. “We made up quite a few bands in our music section - fictional interviews were commonplace,” Turnbull says as we walk to The Bricklayer’s Arms. “Warp Records were very interested in ‘(ph)Lid’, two blokes from Twickenham who I got to pose as Czech dissident coal miners, who found a keyboard in a skip and decided to make speed garage.”

For a few months in 2000, a young illustrator - one of Lazarides’ friends from Bristol - would come into the Sleaze office to use the photocopier. “There was a picture agency next door, and he would come in for a few hours at a time and quietly draw.” Turnbull said that he could only use the copier again if he drew a stencil of Busta Rhymes for the next cover of Sleaze. That man was Banksy.

“Around that time, Robin started blitzing Shoreditch with his stuff. Robin was one his ‘names’, I think… He was this ordinary-looking bloke, but he was selling these canvasses for £50. He asked me for £190 for a larger one and I said: ‘No mate, I can’t stretch to that.’ One of our advertising girls upstairs bought a smaller one and sold it later for £45,000. I reckon I’d be £300,000 better off if I’d bought it. Still, he gave us the Busta print for free.”

Soon, Lazarides was joined on the masthead by maverick designer Scott King and new editor, Neil Boorman - the man behind Shoreditch Twat, a similarly snot-nosed club guide handed out at the 333. Though Boorman did what he could to bail Sleaze out of its sales slump, when he started at the magazine in 2001, it was already terminally ill.

Zine-Finity And Beyond.

Charting Sleaze Nation’s brief but complex evolution tells you a lot about the realities of post-millennial publishing. Though retaining its puke-y, subversive charge (one of Boorman’s best issues was dedicated to the art of wanking; from expert insight into overcoming self-pleasure addiction to a study into history’s great masturbators) its final years saw more big-biz sycophancy than at any point in its lifespan. “I was under no illusion after a couple of months, after the honeymoon period, that the publisher wasn’t actually the publisher of the magazine. All the brands that advertise with it were,” he tells me.

For all his sarc, Boorman was an ethical editor (“I absolutely did not have emaciated models looking like they’d just done heroin in the magazine”), but his conscience, he admits, was to the magazine’s detriment. Sick of the sample-size scene, he ended up casting himself for a men’s grooming story. A thin strip of hair was shaved from his arse downwards by an experimental body-pattern artist, and the resulting pics made their way onto newsstands. “It was a brilliant contradiction. We wanna be in the window of your shop, because we love the fashion. But also, fuck you. Two fingers up, it was like a kind of kiss, you know, a kiss, but also a punch in the face.”

For a while, everything Boorman tried to do to woo the moneyed and powerful seemed to backfire. He had one issue party catered for by Cornish Pasty giants, Ginsters. “We had all these super cool, apex Shoreditch-types saying, ‘I’m really fucking hungry, but I can’t bear to eat those disgusting things,’” Boorman explains. “It was such a laugh, you know, what a giggle. But it blew up in my face.”

For another launch — to mark the title’s short-lived rebrand under the simplified moniker “Sleaze” — Boorman organised a mass mag-burning party, where punters would throw copies of The Face and i-D onto a bonfire. On the cover of Sleaze Issue One was a crumpled picture of Victoria Beckham being engulfed in flames above the headline, “Celebrity Burnout”.

The hype effort worked, albeit briefly: sales spiked and, for the first time, they’d found common ground with Burberry. Despite this, Swinstead and Dewhurst encountered difficulties with their distributors and, in 2004, called time on Sleaze Nation.

So, where do we go from here? What does Sleaze’s story prophesize for the rest of the magazine industry? Boorman seems to think that in future, style titles will be run by brands like adidas and Supreme, who can inject passion, money and cultural heritage into content. It’s not about publishing houses suddenly becoming more engaged with its corporate partnerships, but the corps taking over altogether.

“I actually think brands are in a better space to publish magazines than publishers, because the ultimate kind of credibility and authenticity for them nowadays comes from populating culture, rather than emulating it,” Boorman says. “There’s no mystique to it any more. It kills me to say it, but it might happen.

“Bauer or IPC

Post-Sleaze, for a writing project he’d dubbed “Bonfire Of The Brands”, Boorman took his pyro-party idea one step further, throwing everything physical he owned into an inferno and living for a year without commercially-branded possessions. “That was a result of one too many meetings - you know, literally on my hands and knees begging the UK franchise owner of Spliffy for a double page spread in Sleaze Nation,” Boorman regales. “I was really conflicted at that time: I love gear and love nice things but at the same time, boy, the costs professionally, financially and emotionally with acquiring all that stuff and being around it all the time is, for somebody like me, was just way too much to bear.”

As senior editor at the sadly-deceased Arena for seven years after leaving The Face, Beale’s journalistic pursuits got darker and more immersive, too. For one article, he had £20,000’s worth of plastic surgery done - his teeth carved down and veneered, his man-knockers chopped off, his fat sucked. Needless to say, he put it all on the company card.

It’s not surprising that the magazine’s editorial alumni went to such lengths for their work after cutting free from Sleaze. From the start, Swinstead and Dewhurst granted staff members boundless creative license, encouraging them to shit down the necks of the ridiculous. “Swinstead let a lot of loose-cannons loose, and they did a really good thing from being let loose,” Turnbull observes.

In stark contrast with today, in the 90s you didn’t need to be on The Tatler List to get a job at a magazine. To get in with the Sleaze lot, you barely needed access to running water - just soaring ambition and some sort of drug habit. It probably helped if you still hated your parents, too.

The Sleaze Is Dead. Long Live The Sleaze.