George Lois, RIP

The news that legendary New York art director George Lois died has been rippling through the design and publishing worlds this week.

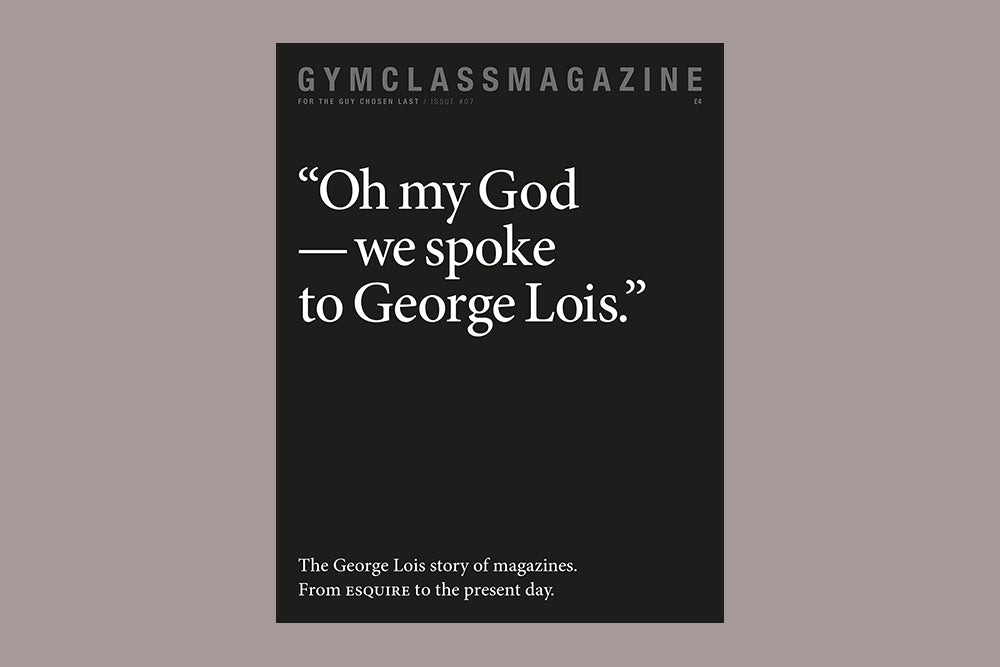

To mark his passing, we’re honoured to run the following interview with Lois. Andrew Losowsky met him in 2010 and the resulting piece ran in the seventh issue of Gym Class Magazine. Andrew suggested the cover design too (above), a gentle parody of one of Lois’s incredible 60’s run of cover designs for Esquire. They talk about the cover’s origins during the interview.

Andrew recalls, ‘The interview was a delight—though I can’t take credit for any of it, really, all I did was sit back and enjoy the show.

‘Before the interview, he had sent Steven of Gym Class a note saying how much he was looking forward to it, because “magazine geeks are my people.” George Lois was a genius, a talker, a showman, and he was one of us. Thanks George, for everything.’

We post the entire interview, without edit, as it originally appeared—including the original introduction that is as good an overview of Lois as I’ve seen. Over to Andrew…

He dressed Muhammed Ali as St Sebastian, and put Richard Nixon in the make-up chair. He showed Hitler as an old man (with the tagline “Can I come home now?”), and made Andy Warhol look like he was drowning in a can of Campbell’s finest. Want to see some of the greatest magazine covers of all time? Take a look through Esquire’s archive, from October 1962 to September 1972—all of which were the creation of one George Lois.

Lois’s career was much more than as a celebrated cover designer—he was one of the most famous art directors at the height of the Mad Men era (a show he recently declaimed in Playboy for not sufficiently celebrating his work, and for over-exaggerating workplace drinking). He claims credit for “I want my MTV”, for saving Tommy Hilfiger and USA Today, for getting four senators elected, and has so far written nine books about his work and methodology.

He is also a big talker. In this exclusive interview for Gym Class, he describes his high school as ‘the greatest seat of learning since Alexander sat at the feet of Aristotle,’ claims to have predicted the Vietnam War, and says that if he had the backing, he’d make a magazine today that would sell millions.

Maybe it was, he did and he would. Meanwhile, some people, who were there at the time, have accused him of exaggerating his role in the creation of many of his most celebrated images.

Though they feel aggrieved, for the rest of us, it doesn’t seem so important. As George would say, it’s all about the bigger story. And George sure can tell a story.

Does it annoy you that people want to talk about Esquire?

It’s repetitious, but it’s amazing how many times I answer the questions, and they still say, George Lois who was the art director of Esquire in the 60s. They don’t understand I was never an art director at Esquire, I’m an advertising guy.

Did you pay much attention to magazines growing up?

I’ve appreciated editorial design since I was 14 years old, as a student at Music and Art High School. It was an incredible high school. I call it the greatest seat of learning since Alexander sat at the feet of Aristotle.

I was lucky enough to be sent there by my public school teacher, I had no idea that the school existed. She came up to me one day and she said, “George, do you have ten cents to get the bus to this school right now? You'll take a test when you get there, and you'll pass easily.” She handed me a big black string portfolio, which she had gone out and bought for two dollars—which was a lot of money back then—and she opened it up and she said “Show these drawings.” She had about a hundred of my drawings that she had saved from since I was nine years old. She was saving them for herself, but somehow she realised I should go to this new high school, and she sent them with me there.

And that school changed my life, because I got an education not only in design but in the history of design. I don’t think connoisseurs of the history of art or design know what I knew when I was 15 years old. The work of the legendary Dr MF Agha was highly studied, and Alexey Brodovitch, and Bradbury Thompson, and of course Paul Rand. He was my hero then, I was 14 and he was probably 26 years old, and he was doing ads that when you glanced at them, you knew he had done them.

Whenever he had an ad, I cut it out, and would hang it up in school and we’d talk about it. He had this reputation as a designer who didn't take shit from anybody, he had a tough, tough reputation. He did his own work, wrote his own copy. He became a great hero of mine, not so much for the work though the work was wonderful and very unique, especially for back then, but he was a hero because I could see that you could be a designer, a so-called Commercial Artist, and make a living while doing great work.

I think there was more study and appreciation of editorial design than there was of anything else, certainly more than advertising. Editorial design was the most exciting thing to look at.

Did you want to design more than just the covers at Esquire?

I always felt guilty about not taking on the design of the complete issue of Esquire, so that the visual contents could be truly in tune with my covers. But designing a great issue each month is a 24/7 job, and I was at that time, day in day out the creative force of the ad agency that I was head of in 1960, that triggered the advertising revolution. I was up to my neck in work, I had no choice.

As it is, I basically created most of my Esquire covers at home in the middle of the night or many times walking back to my ad agency after meeting with Howard Hayes, the editor of Esquire. We would meet at the Four Seasons restaurant every month, it was a client of mine, we would have lunch there once a month, and he would give me an outline of what was in the next issue. I almost never had the articles to read, there was a long lead time I had to adhere to, he’d tell me what was in each issue, and many times walking back from the ad agency, a five or six block walk. I would get the idea for the cover. It would happen to me maybe half the time.

One of the reasons was, I didn’t have any time to waste. Many times, he’d say something, and I’d get an idea when he was in the middle of explaining it. Sometimes I knew the cover in my head before he finished explaining the issue.

For instance, the very first issue. The reason Hayes ever talked to me about covers? In January 1960, we had started the second creative agency in the world, Papert, Koenig, Lois, the first time an art director's name was on the masthead of an ad agency, and we were successful within two weeks. We became a hot agency, there were articles in magazines and in the New York Times at least once a month about an ad campaign that I’d created.

When Hayes called, he had just been given the editorship of Esquire. Something made him call me up, and he asked to have lunch with me. I said, Sure. We met and he immediately asked if I could do him a favor, to help him do better covers. I had never done a magazine cover in my life, but to me it was like another job, it was a communications problem.

He described their creative process. It was what I call “the group grope”. They'd get together and have discussions about what they thought the cover should be, and they’d all have ideas, and they’d comp up two or three or four, and show them to people.

I said, you clearly don’t have anyone there who can do it, so you have to go outside and get a designer. I gave him some names, and he said, You’ve got to do me a favor, do just one, because I don’t know what the hell you're talking about.

At that point I said, OK, when's it due. He said, Next Tuesday, but let me give you time, I’ll give you another month to do, and I said, No no, tell me what’s due Tuesday—I think this was on a Thursday—and I’ll get you a cover, describe the issue.

So now we're getting to that first cover. He gives me this and that, and then he said, he had almost forgotten, Oh yes, we're putting in a photograph of Sonny Liston and a full page of Floyd Patterson.

I knew immediately what to do. Floyd Patterson was the champion of the world, Sonny was the challenger. Floyd was an 8-1 favourite, big favourite, everybody said he would destroy Liston, too fast, great left hook. And when Hayes told me that they'd include those two photographs, and that the issue would come out five or six days before the fight, I said, OK terrific. I knew what the cover would be. I would call the fight.

I knew at the time that the sportswriters were all wrong. And when I was on my way back from lunch, if I’d had a cellphone back then, I’d have called a photographer from the street, but I waited until I got back to the agency, called a guy and said, St Nicholas Arena is still there, they’re going to tear it down, let’s get a guy that looks like Floyd Patterson, we’re going to shoot him Saturday or Sunday, and we're going to show Floyd Patterson dead, not only knocked out, but dead and with 20,000 people gone, the whole place empty. A metaphor for life—when you’re a loser, you’re left for dead. I knew the second Harold told me, that would be the cover.

What would have happened if I was wrong? Harold called me up and he said, I never saw a cover like this in my life. I said, Yeah, that's my job. He said, You're calling the fight. I said, No shit. He said, Everyone says Patterson's going to win. I said, They’re wrong. He said, You're crazy. I said, No, you’re crazy, because you're going to run it.

If we were wrong, the whole country would laugh at us. There was no reason to say yes, other than he had a feeling about it, and about me, and that maybe this crazy Lois is right, and if he's right, it's dynamite.

I found out years later that the publisher, Arnold Gingrich, told him no way, we’re not going to run that cover, and Harold, who had only just become the editor, said that if they didn’t run it, he would quit. Talk about balls. People say, George, you had big balls doing those covers. I didn’t have big balls—Harold Hayes had big balls running them. I would do a cover sometimes, and he'd say, Wow what a cover, and I’d say, Harold, this cover is going to make big trouble for us, and he'd say, Yeahhhh! He loved it every time there was a real controversial cover that was on the nose and exciting and dramatic. It said that Esquire was a hot edgy magazine. When I said there'd be trouble, and he knew it, he'd say, Yeahhhh! He loved all the covers, but he especially loved the ones that made trouble.

Did you ever go into the Esquire office?

I only remember visiting the Esquire offices once. He called me one afternoon, he said, George, you gotta do me a big favor. Can you do something for me at six o’clock? I said, Y-yeah, sure, if you really need a favor. He said, Good.

Why did he want me to go to Esquire? I didn't want to talk to the other editors, or the designers, or the ad sales people. They were the enemy almost. He said, We have a softball game in Central Park. I said, What kind of a team do you have? He said, We're good! I said, Do I have to? He said, Please, we need you.

So I go over there with my glove and my sneakers, and I could not believe it. I looked at the team. The third baseman was Gay Talese. The second baseman was Gore Vidal. It was not a team of athletes. I said, Oh my god, they're all literary geeks. He said, No, no, we’re going to have fun.

Now I’m serious about playing softball or basketball. I don’t screw around, I play with great ballplayers, I’m a good athlete. I said, Harold, this side is terrible. He said, No no!

We went over and played The New Yorker, and I think we lost 18-3, and the only reason we got three runs is because I hit three homers. I don’t remember being there for any other reason.

In the early 2000s, Vanity Fair did a big story about 1960s Esquire, and they wanted to take a photograph of all the people still alive from back then, 30 of us maybe. We all went to the Four Seasons for a photograph, and I met 25 of them, whose names I knew well, for the first time. They were toasting me because they were big fans of the covers, and they knew that the covers literally saved the magazine’s life.

When you ask about what would have happened if Patterson had won... they probably would have gone out of business in a couple of months. I heard when posing for this Vanity Fair piece that many of them weren’t expecting paychecks that month. The magazine was deeply in the red.

The only reason I knew things had been bad was because, a few years after I started doing the covers, they had a big party because the magazine had gone from being deeply in the red to being $2m in profit that year. I didn’t go to the party, I can't stand them, but that’s when I realized that all the time I was doing the covers, they were in deep, deep shit.

When the staff saw my first cover, they said, Oh my god this is a death knell, because Patterson's going to win, it’ll make us look stupid, and that’ll be the end of the magazine.

How did you decide what the subject of each cover would be?

Harold would tell me what was in the issue, he didn't have any notes, he didn't give me anything written, he knew I just wanted to hear it. If he said something that interested me, I’d say, Wait, say that again.

He never said to me, The topic of the issue is this... but there were some times when he said, This issue is basically going to be on the new american avant garde art movement, so I had to pay attention to that, and my answer was to have Andy Warhol drowning in a can of Tomato Soup.

Or there was a very important story a year after Jack Kennedy was killed, called Kennedy Without Tears. A writer was analyzing Kennedy as a president. So what I did was a cover with tears, where a man's hand wiped a tear off a photograph of Kennedy. You don’t know whether the tear was the photograph crying, or the tears of the reader.

There was a deal I made with Harold after the first cover. He said, George you gotta keep doing the covers. I said, Sure, terrific, I think they're fun, but you've got to understand I have an ad agency, I don’t have the time to run over to Esquire and have idiot conversations with ad sales people or publishers or any of the other editors. I think I trust you but the second a cover is turned down, I’m gone. He said, You’ve got a deal.

One day he said, It’s Christmas coming. I said, Yeah, where you going? He said, Can you do me one favour, could you make the cover Christmassy?

It was a funny request. I looked him in the eye, and I said, You got it. Because the minute he said it, I knew what I was going to do.

At the time, it was an incredibly rough time in the race relations, there were the black panthers, it was the Jim Crow era, a black guy in the south had to drink out of their own soda fountains, couldn’t go into a restaurant to eat... Racism was terrible in America. If I was a black guy, I'd have been a terrorist.

I was thinking about the whole racial thing at the time, and I thought immediately, I’m going to show Sonny Liston—who was a terrible man, he was the champion from the first cover I did, and his reputation... he was a labor goon, he would beat up strikers, he worked for the mob. I was going to get him to pose with a Santa hat on his head.

When I sent that to Harold, he knew he'd struck gold. He also knew they’d lose a dozen ad sales accounts. They had a lot of southern advertisers, clothing mills and so on down south. After it came out, there were senators and congressmen holding it up, saying, Look what Esquire is doing, they are fomenting racial tension, showing a negro as Santa, asking for trouble. When Harold saw it, he said, Wow. Yeahhhhh!

They lost a dozen accounts, and people were going crazy there, but Harold knew they would get other accounts. A month later, they did.

Why didn’t he run your first Vietnam-themed cover?

Harold gave me whatever the input was, and I came back and I showed him a photo of a GI.

I had read in the paper a couple of days after we talked, a tiny piece on like page 32 of the New York Times, 100th GI killed in Vietnam, and I knew then that we were going to go into a fully fledged war. It had started as it always did, with military advisors, CIA advisors. I wanted the Pentagon to send me the photograph of that 100th GI and they wouldn’t give it to me, so I used the photo of me from the Korean War as a comp, with the GI looking the reader in the eyes, and saying “I’m the 100th GI killed in Vietnam. Merry Christmas.”

I sent it to Harold, and he said, Wow, George, you think it’s going to be a big war? I said, This is going to become bigger than Korea. He said, Wow, what a cover. I said, You’re chickening out? He said, No, I’m not chickening out.

He came back a couple of days later and said, George, I dont know how to tell you this. I said, You're chickening out. He said, No, there's all kinds of political reports about us bringing the advisors home, the politicians are talking about how we can’t go any further in this thing, I think that by the time the issue comes out, this so-called war is going to be over.

So I gave in. Harold looked me in the eye about ten times after that, and said, We should have run that cover, George. He literally thought the war would be over so fast. As the reports came in, 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 dead, he’d say, You were so right. But I never held it against him.

There was one other cover, 1964 or 65, that he didn’t run. There was a big story about Eldridge Cleaver, a prominent Black Panther. Things were really getting touchy in America, they were building concentration camps to put black guys in, trust me.

I did a cover with the Aunt Jemima pancake logo. The logo was a “Mammy”, black, chubby, with a bandana—it was a real stereotype. It was a charming drawing, but in light of what was going on, it was racist.

So I took the logo and I had her look at the camera, and in her right hand, I placed a cleaver. It basically said, Aunt Jemima is Angry, she’ll come and chop your balls off. When Harold saw that, he got scared. He said, George, we’re going to get in such political trouble. I didn’t fight too much, we’d run six or seven killer covers, but he did chicken out. Years later, I said, We should have run Aunt Jemima with the cleaver, right? He said, I’m not sure about that one.

I had to hand it to Harold. He was enormous. Every time I’d call him up, he’d say, Wow what a cover. Like the Lt Calley one (Lois photographed the officer who ordered the My Lai massacre, Lt William Calley, smiling at the camera while surrounded by sad Vietnamese children), I said, We’re going to have trouble with that cover, and he said, Yeahhhh!

Did you feel the content of the magazine lived up to the covers?

Sure. My covers wouldn’t have worked if they didn’t. Hayes was the greatest magazine editor ever. He is the reason that the 60s are known as the golden age of journalism. My covers promised a hot shit magazine. If you bought it, and you said, Dull, boring, dull, as you turned the pages, the cover would have been ludicrous.

How did the typographic ‘Oh My God’ cover come about?

I had done another cover ready for that one, I don’t remember what it was. I knew that John Sack was writing a story about being with M Company, that he had joined them as a civilian for their basic training in Fort Dix and followed them all the way to Vietnam. I asked if I could get an excerpt. Harold said, I’m going to get it very shortly before publication. So I did another cover, and I called Harold about something else, and he said, Oh by the way I just got John Sack’s article, would you like to read it?

He sent it over with a messenger. I’m reading it, going, Wow wow wow, and there was the line: ‘Oh my god, we hit a little girl.’

I called up Harold, and said, Do I have time to do a different cover? He said, No, we’re going to press tomorrow. I said, What happens if I give you a cover in three hours? He said, What do you have in mind? I said, Just hold your horses, I’ll send it over.

I set the type, it was pretty simple. I had my assistant run it over to Esquire, Hayes called me and said, Holy shit. What a cover. That’s how that came about—me reading it, I saw the line... and that became basically the first true anti-war magazine cover at that time.

It was a killer cover. They were standing up in Congress, holding up the cover, saying how dare Esquire magazine say that American boys could kill innocent civilians. They bombarded Harold and the magazine. He said, Are you shitting me? You put 18 year olds out there, they’ll do anything.

I was in the Korean War, all kinds of shit was going on around me. Did I partake in it? No. Did it disgust me? No. Did I see it? You bet. I saw it at least ten times in Korea. But they're standing up in Congress saying, Young American boys, blah blah. Are you shitting me? Look at what we did to them in Iraq, my God.

One of the great things about Harold was that he wasn’t political, he wasn't a left winger. I’m left wing, always have been, that didn’t bother him, in fact he loved it. I never tried to do anything so left wing it could be called Commie. But when I did Ali as St Sebastian, I combined race, religion and war, in one cover. Said everything that has to be said.

Your final Esquire cover featured a naked Jack Nicholson. It didn't run because his agent wouldn't allow it. Have we handed over too much control to celebrities and their people?

A lot of my covers were brutally critical, others made people look great, but a celebrity should not dictate the cover image. It’s absurd to create an image to please a celebrity—you want to please your readers.

If I was doing covers today, I'd still be doing great covers with celebrities. I had Sonny Liston pose as Santa Claus, I had Ali pose as St Sebastian, I got Roy Cohn (the leading attorney who prosecuted Senator Joseph McCarthy's communist witch hunt), the piece of shit that he was, posing with a halo. Terrible man, and when he was walking out the studio, he said, I guess you Commie sons of bitches are going to use the ugliest one, and I said, You bet your ass, I hate you.

But the point is, you can creatively do great covers with celebrities, sometimes with their permission, and they'll go for it, or without their goddamn permission, and do covers that really show the drama and the power of the magazine.

What every magazine has done is play the game, pick the flavor of the month, put about 12 blurbs around him and sell the magazine. That's the wrong way to sell a magazine. What I did was design a package for Esquire each month, and you might hate it, you might love it, but you’re knocked on your ass, and you say, I gotta buy this magazine.

You said recently that if you were a young guy today, you’d make a magazine. Why?

If I had the backing to do it, I’d love that - and not have to listen to anyone or anything else. Not listen to the ad sales guys, not listen to anybody saying, George be careful.

Bull. Shit. I’d do a magazine that would knock you on the goddamn ass, and millions of people would come to it because they wanted that magazine. It would find its own market somehow. I have two or three magazines in my head for the last ten years I'd love to do. When things happen, I say, Wow, what an article that would have been.

The secret of making a great magazine is not to create it for your advertisers or your readers. You create magazines for yourself, you and your entire editorial design culture should create a magazine that you love, that you think is important. With no inane marketing research, no dumb reader studies, no nothing, just a magazine that you know is sharp and written for intelligent people like yourself. A magazine that the masses will find a thrilling experience each issue.

What magazines do you read today?

I read every word of The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, and I’m a lefty, so I read every word of The Nation. But I look at every magazine, I buy dozens of them, look through them and throw them away. I'll buy ten magazines, give the guy a hundred bucks, bring them home, go through them so fast you can hardly see my hand move, then I'll leave them for my wife, maybe she'll keep two or three, and throw the rest of them away. I just want to see what's going on.

People say, will magazines ever be dead? The difference between reading a magazine in your hands or on a computer is the whole visceral feel of having a magazine in your hands. If you put it on your knees, it’s a lap dance. It’s better than a woman's ass sometimes. It’s the visceral fun of looking, being surprised, even by a good ad, by great editorial design. That’s the opportunity.

The interview took place in 2010. Thank you to writer Andrew Losowsky and publisher Steven Gregor (Gym Class Magazine) got permission to republish.

Gym Class is no longer published, but a second issue of its new iteration Jim is due in early 2023.