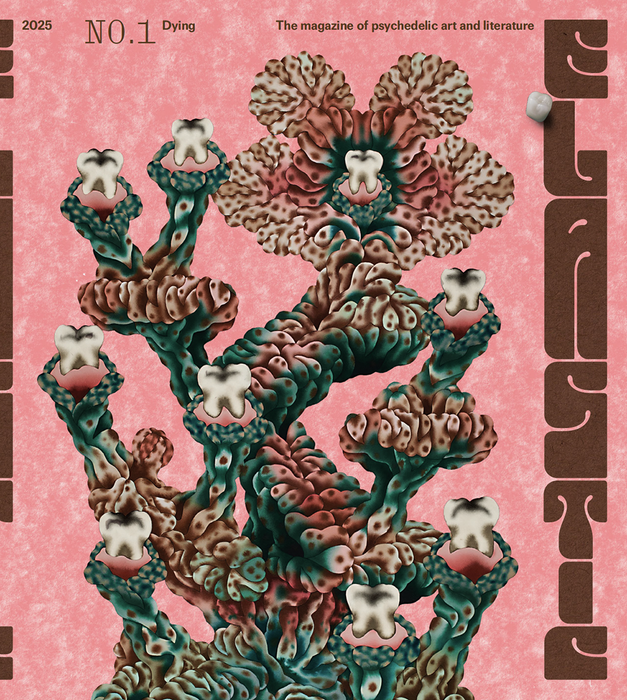

Hillary Brenhouse, Elastic

Hillary Brenhouse is a Montreal-based writer and editor who has just published the first issue of Elastic, a magazine of psychedelic art and literature. It’s made an immediate impact at magCulture for its bold intentions and brilliant design.

Elastic isn’t Hillary’s first magazine; she was previously he editor-in-chief of Guernica magazine, and her own work, on the body and broken capitalism, has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker online and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

She explains the origins of the new magazine, noting that, ‘The first psychedelic era was a time of dislocation and crisis, and also a period of radical artistic innovation. The same can be said of this current psychedelic era.’

What are you doing this morning?

This Monday morning, like most mornings, I’ve done the following: wake up when my toddler wakes up, thank my husband greatly for taking her to daycare, roll over, sleep for another hour, and then drag myself to the Depanneur Café on an empty stomach.

The Dep Café is a coffee shop and a Montreal institution and it’s down the street from my apartment. I’m one of a cluster of regulars who treat the place like their office. In fact, we call it “the office,” and yet it’s laughably un-office-like. There are dusty couches and little tables that are much too close together. In the front room, where we all like to sit, there’s one single electrical outlet for plugging in. And there’s live music, from 10am to 6pm, every single day: jazz pianists, French Canadian folk singers, flamenco guitarists. The outlet, which I always try to snag, is right next to the performers and thus to the noise. Many people are understandably appalled when I tell them that I do virtually all of my work in this environment.

But I am a community person. I would wither away if I made myself go through the day at home, in isolation, or in a silent co-working space. And I need a bit of chaos. So here I am, with the morning matcha latté that is effectively my breakfast, preparing a class on psychedelic writing that I’ll give at a literary festival in Denver later this week and waving at everyone I recognize who comes through the door.

Describe your work environment

I’m seated at the two-person table that’s both next to the electrical outlet and the piano. There’s a jazz trio playing and I can feel the vibrations of the bass. It’s finally June, which means that our eight-month winter has come to a close and the city is buzzing with sex and relief. I’m in the heart of Montreal’s Mile End neighborhood, one of its loveliest, and outside the open window people are drinking coffee on the newly erected terrace, chatting, smoking, locking up their bikes, wearing short shorts. I used to be particularly fond of the view because the Drawn & Quarterly bookstore was directly across the street, but it moved to make way for a pilates studio. It didn’t go very far, though; now the bookshop is several doors down, and I go there and peruse the titles when I’m looking for inspiration.

The café is about half full this morning, but by 3pm it’ll be packed. On Monday afternoons, a multi-piece Klezmer ensemble—violins, piano, a hammered dulcimer—plays for two straight hours and it’s especially good and especially lively. On a recent Klezmer Monday, the coffee shop broke out into a dance party. I was sending initial emails to potential contributors to Elastic’s second issue at the time, and those messages definitely had ecstatic dulcimer energy.

Which magazine do you first remember?

I used to buy copies of Cosmopolitan at the grocery store and pretend they were for my mother. I couldn’t believe what they contained and I loved them dearly. Some people got their earliest sexual education by watching scrambled pornography. I read Cosmo in bed at a time when I could barely understand it. What I was sure of is that the women were beautiful and that, yes, desperately, I wanted to know how to please my man in seven moves (I did not have a man; I was barely ten years old). In other words, magazines began for me as a guilty pleasure, and they’ve retained something of that: I keep my sizable mag collection in a couple of drawers and sometimes, when no one’s home, I’ll spread them all over the floor and caress them. They make me feel giddy.

Aside from yours, what’s your favourite magazine/zine?

One of my favourites was the American literary magazine Black Clock, which was published out of the California Institute of the Arts and is now, very sadly, defunct. Black Clock was its own radical universe. It published unconventional writing by unconventional writers, many of whom were early in their careers—people like Miranda July, Don DeLillo, Aimee Bender, Maggie Nelson, and Jeff Vandermeer. Every issue was boldly designed and unexpected and had this scrappy, fearless feeling. I think that the magazine’s editor, the novelist Steve Erickson, was more invested in granting his writers’ freedom than he was in achieving someone else’s idea of perfection. Some of the themed issues I’ve never seen are the stuff of legends; one of them was composed of chapters that never made it into the novels they were intended for and wound up on the cutting-room floor. Black Clock wasn’t afraid to be the cutting-room floor.

I’ve taken quite a lot of inspiration from the issues I’ve read and the stories I’ve heard about how they were made. This is the type of publication that most deeply appeals to me: one that’s provocative, that has a strong and cohesive vision but trusts its contributors to arrive there in whatever far-out way they’d like, that takes risks and doesn’t overly explain or apologize for them.

What other piece of media would you recommend?

It won’t come as a surprise that I’m especially drawn to things that play with narrative structure and experiment with time. A couple of months ago, I was in the Bay Area to hold an Elastic launch party and was lucky enough to attend a movie at The Roxie, a historic San Francisco cinema. The lit mag ZYZZYVA and author Ingrid Rojas Contreras run a series where they’ll invite a writer to pick a film and then screen it (and discuss it.)

That night, writer and journalist Lauren Markham had chosen ‘Rivers and Tides’, a 2001 documentary about the work of landscape artist Andy Goldsworthy. I had never seen it before and it really moved something in me. Goldsworthy painstakingly assembles sculptures out of branches, snow, grass, stones—and then watches them fall apart or get blown away by the wind or swallowed by the sea. It’s an astounding meditation on the circularity of time and the ephemerality of all things. I would highly recommend.

Other stuff that I’ve watched over the past year, and loved, that deals with shifting narrative perspectives: the miniseries ‘Station Eleven’ (2021), which is based on the novel by Emily St. John Mandel, and the Japanese film ‘Monster’ (2023).

Describe Elastic in three words

Strange. Familiar? Strange.

What does psychedelia mean to you, and what brought you to launch a magazine about it?

For years before launching the magazine I had been going to electronic music festivals, very many of which featured makeshift art galleries focused on psychedelic art. Everything in these galleries looked the same to me: fluorescent mandalas, contorted mushrooms, Rick and Morty running through spacescapes. I felt convinced, as someone who’s interested in the psychedelic experience, that psychedelia was, is, and might be a much more expansive category than the narrow, cartoonish version of it that’s taken root in the popular imagination.

I began to toy with the idea of making a magazine. And at what was a very critical moment in the genesis of Elastic, I came across a feature in T: The New York Times Style Magazine written by the cultural critic Emily Lordi that’s called ‘The Radical Experimentation of Black Psychedelia.’ We’ve come to associate the psychedelia of the sixties and seventies with a small group of white dudes, but Emily here demonstrates that Black artists and thinkers were at the leading edge of the first psychedelic movement.

That piece was foundational to this project. Lordi’s description of psychedelic art really rejoined the one that was circling my own brain; she writes about work that takes “an elastic approach to time,” that draws “sublimity and absurdity from everyday sites,” that is a “combination of scale and mystery,” that is “lush and immersive, dreamlike and daring.” She also categorizes a range of contemporary art as psychedelic, which gave me a big push forward. (I asked her, on a call, if any of the living artists she calls out were bothered by that categorization. No one was.)

I realized that Elastic should attest to the tremendous breadth of psychedelia both by publishing a truly rich, diverse body of newer pieces and by spotlighting an underrecognized creative archive.

What can the world learn from psychedelia today?

The first psychedelic era was a time of dislocation and crisis, and also a period of radical artistic innovation. The same can be said of this current psychedelic era. Elastic doesn’t draw a firm distinction between contemporary and historical psychedelia. The idea of the magazine is just to recognize the sheer range of work that was and is being made in this register. Day-Glo mandalas and 1960s poster art aren’t even the tip of the iceberg.

It seems to me that psychedelic art is very powerfully suited to this moment. Every one of us has experienced states and conditions that can’t be described straightforwardly or linearly. And we need to be able to communicate those states to each other. One of those states is grief. Grief is extremely psychedelic; it doesn’t occur in a straight line; it’s multidimensional; it’s subatomic; it scrambles narrative. How else to represent grief on the page than by shattering conventional notions of time and space or blurring waking and dreaming life? And this is what the writers and visual artists in the pages of our first issue, which is on the theme of dying, have done. They’ve taken their own bizarre, singular routes to the center of grief and childbirth and chronic pain and transition and ego death to try to adequately and vividly relate these things.

As I write in my introduction to the issue, it often feels like our twisted present can only be contemplated clearly through a warped lens. Which is to say that I think psychedelic art is capable of capturing inarticulable things about ourselves and our environment. Our contributors, contemporary and historical, have responded to the world we live in, the here and now. They’ve flipped it upside down and turned it inside out, but it’s still recognizable.

(All of this brings so many great books to mind. Check out, for instance, the novel ‘Open Throat,’ by Elastic contributor Henry Hoke, which grapples with the climate crisis and is narrated by a queer mountain lion roaming the Hollywood Hills.)

We love the way the pages have been designed to flow from one to another, blurring the individual stories together. How did that come about?

That is the work of our genius creative directors, the designers Chloe Scheffe and Natalie Shields. Their design system functions such that reading the magazine from beginning to end feels itself like a psychedelic journey. They’ve dissolved the typical boundaries and so, as you point out, the pieces tend to blur into one another. Relatedly, they play with that line between the familiar and the unfamiliar, producing this kind of off-kilter sensation. You come across these little fragments and then, later, find that they all belong to the same big work of art. Or you’re presented with one big work of art, and then later reencounter it in different forms—chopped up and transmogrified. You’re constantly asking yourself, “Wait, where have I seen that before?”

What’s incredible is that it’s not just the design that engenders this feeling: the pieces of art and writing really did come together into something of a collective half-dream or hallucination. We didn’t push any of our contributors toward particular subject matter or attempt to maneuver them, and if we ever did, they didn’t listen. They let themselves go and we followed. And we were astounded, when they submitted their work, by the resonances that cropped up between the drafts. Both Aimee Bender and Gerardo Sámano Córdova wrote about a tooth plant (WTF?), which is why we asked the painter Matthew Palladino to conceive of one for the issue’s cover. The protagonists in Anne de Marcken’s piece and in Shruti Swamy’s both follow a horse. And I could go on and on and on.

Increasingly, as it was being assembled, the issue came to feel like a single strange trip. When that started to make itself clear to me, a lot of things clicked into place; I began to make decisions in service of that trip. To give a simple example, I knew, when I received Melissa Broder’s poem, that I would place it last, because, to me, it conjures that headspace you might arrive to at the end of a psychedelic voyage: I am everything and everything is me.

Please show us one spread that sums up how the magazine works, and gives a sense of what the reader can expect

It’s impossible to sum up this magazine in a single spread! I’ve chosen this one because I think it immediately communicates to the reader what I mean when I say “psychedelic art beyond the cartoon that inhabits the public consciousness.” This is a painting (above) that I especially love by the artist Lola Gil, whose focus is suburban nostalgia and alienation and who often blurs and distorts her subjects through glass. (Her grandma had quite the collection of blown-glass figurines.) It accompanies a fun, form-breaking story by the writer Isle McElroy, who’s always been fascinated by daylight-savings time.

What I love most about this magazine is that everything is working in tandem to create that psychedelic sensation: the art, the writing, the design, the interactions between these. Chloe and Nat have reimagined psychedelic design for our current age, playing with repetition and patterns and altered perception in their own way. As you see in this spread, they’ve brought in scans of vintage paper, which create the illusion of textured backgrounds. Across the magazine they’ve introduced hand-painted photo collages posing as digital renders and the idea of misprint, allowing things to overlap and collide into each other. And they settled on a primary typeface—Focal, by Commercial Type—that references 1970s phototypesetting. Greg Gazdowicz, who developed it, writes, “I had an idea of a typeface existing in an uncanny valley of something familiar being printed, overprinted, or xeroxed and copied over a few times.” He was aiming to achieve this impression of something “familiar yet slightly off,” which is exactly how I might describe the whole project.

The design system takes it most extreme form in several “interstitial pages” that are scattered throughout the issue, and I couldn’t help but include one of those spreads here, too. The designers really went for it with these pages and they’re some of my very favorites.

What has publishing magazines taught you that may be helpful to anyone else planning to launch one?

Trust your contributors to help you achieve the beautiful, cohesive vision you’ve conjured on their own terms and allow them to surprise you; doing so is a gift that gives both ways. Also, it’s perfectly normal to feel, every day, for many months, like you’re plugging holes in a sinking canoe, even if your magazine is doing well in the world. Get some rest. It will still be afloat in the morning. (I’m still learning this part.)

What are you most looking forward to this coming week?

Early Wednesday morning I leave to Denver, where I’ll participate first in the Lighthouse Writers Workshop’s Lit Fest and then, several days later, in Psychedelic Science, the largest psychedelics conference in history. I’m especially excited about the literary festival. I’ll be teaching a class on psychedelic writing; to my knowledge, Elastic is the only initiative that’s seriously contemplating the notion of psychedelic literature. We’ll review several pieces from the magazine and the techniques that some of these writers have used to portray altered states of being on the page. The class is full, it seems that there’s an actual interest in these things, hallelujah.

I am very passionate about print, but sometimes I think that I mostly made a magazine so I could go places and hang out with people.

Editor-in-chief and founder Hillary Brenhouse

Creative directors Chloe Scheffe and Natalie Shields

Buy your copy from the magCulture Shop