Farewell, The Happy Reader

Earlier this week in London, a launch party heralded the final issue of The Happy Reader. Across 19 issues, the magazine had established a unique niche for itself, applying the editorial inventiveness of its sister publications to celebrating the joy of reading books.

Unlike those other magazines—Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman—The Happy Reader was funded by a third party, Penguin Books, who decided to pull the plug on the project. Nobody can be quite sure what the story behind that decision was, but the magazine will be sorely missed by its many regular readers.

It seems the excellent Happy Reader email newsletter is set to continue, and when asked last night about the unsatisfying total of 19 issues, editor Seb Emina suggested it left the door open for an issue 20 at some point in the future. Fingers crossed!

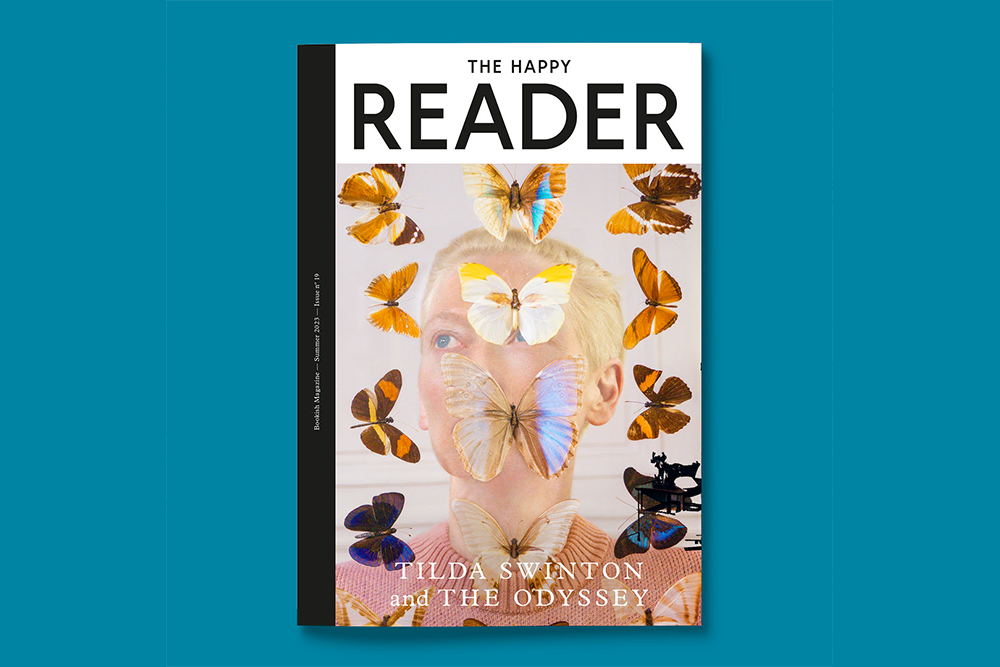

Meanwhile, all you happy readers have one last issue to enjoy, and it certainly goes out on a high, earning it Magazine of the Month status for July. The guest interview is with Tilda Swinton, the featured book ‘The Odyssey’. If for some strange reason this was to be the first Happy Reader you’ve ever seen, this last issue is, ironically, the perfect introduction: intelligent, fun, and beautiful.

To mark the magazine’s demise we’re posting an interview I did with Seb back in 2016. We were in Singapore for the U-Symposium magazine event, and I spoke to him for a book project that never got realised. I recall we chatted together by a swimming pool inserted halfway up a hotel tower. The interview appeared in Typographic Circle magazine a couple of years later, but has otherwise not been published.

The text hasn’t been updated to reflect recent developments, so please read it as a record of a conversation from seven years ago, March 2016.

How did you come to be editing The Happy Reader?

I’d been writing a fair bit for Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers’ magazines since 2013 when Jop had asked me to write a piece about breakfast around the world, having seen my book, ‘The Breakfast Bible’.

One day I received a mysterious message from Gert asking if I was going to be in London the following week, because they had an idea they wanted to discuss with me. I can't remember whether I was going to be in London or simply made up some pretext to be there.

I had a meeting with them in The Gentlewoman’s office. They told me they'd been talking to Penguin, and asked if I'd be interested in editing a new project, a magazine about books. It was one of those times where, having not expected it, you suddenly find yourself in the middle of a job interview. I had to rush around in my mind looking for things that made me sound like the ideal candidate.

Your attention was immediately piqued.

Yeah, of course. I’ve always enjoyed the commissioning and shaping and editing of other people’s work. I’ve always been a massive reader as well, and quite a bookish person. The idea of doing something that would have a more playful and open approach to reading, rather than the usual literary magazine approach, intrigued me.

Also, the idea of doing something with Gert and Jop and Penguin seemed an incredible opportunity. I gave them a few thoughts on the spot, and talked a bit about some things I've done that seemed relevant, especially ‘A Room for London’, a project at London’s Southbank Centre that I had some involvement with.

Tell us more about that.

Jop and Gert were talking about a magazine that was ‘inspired by’ classic literature, in the sense of using it as a starting point from which to spin off into unexpected and interesting places, which could mean a fashion shoot, or a recipe, or a piece about, I don’t know, farming or something. Magazine features in the orbit of a book.

‘A Room for London,’ was a project I’d worked on with the arts organisation Artangel. It was a one bedroom hotel on top of the Queen Elizabeth Hall by Waterloo Bridge, shaped like the boat that Joseph Conrad took down the Congo in the late 19th century, before he came to write ‘Heart of Darkness’.

We invited a series of authors, artists and musicians to stay in this room with the quid pro quo that they had to produce a new piece of work while they were there.

In the case of the authors, they had to write something of approximately 2,012 words (it was the year 2012) in length. Being in this boat inspired by Heart of Darkness, with a library of books that related to subjects like London and Conrad and colonialism and immigration, ended up begetting 12 pieces that had this cobweb of connection to Conrad’s work. It was thin but it was definitely there.

Was the magazine Jop and Gert described at this first meeting fully formed?

The notion of the cover star and the long interview about reading books and all the things that that gives rise to in the conversation were there. The idea of doing one book per issue, almost acting like that book was the guest editor of the magazine, that was there as well.

You were immediately keen?

I was very keen. A huge amount of stuff that I was interested in coalesced in this one project. It was a dream project. It's about books, but in the sense of standing inside literature looking outwards.

I’ve always had the impression literature is quite an insular world, authors reviewing fellow authors’ books and criticising fellow authors’ books, and occasionally some of them surface in the Sunday papers doing something a bit more popular, but otherwise it's quite inward-looking.

There is that tendency. It's not universal, because you have publications like The London Review of Books or the Paris Review, great literary magazines where you can learn a lot about just about any subject.

But I did feel that there was something else to be done, that there was room for a magazine that existed in the space between literary publishing and the slightly more design-conscious world of independent magazine publishing, of which Fantastic Man and The Gentlewoman are leading examples.

It sounded fun as well, to not have to take everything so seriously, which, with a few notable exceptions, is what literary magazines are in the habit of doing.

Everything you've talked about so far implies enormous freedom, quite an enlightened attitude. To all intents and purposes, it’s another publication from The Fantastic Man team, but with a client, which is very different to the other magazines. Tell us about the relationship with the client.

It’s a very close relationship. When we go into production, which takes two weeks, I base myself in London at the Penguin office, and I sit for long stints with designer Matt Young at his computer, laying out the magazine, throwing stuff together, seeing what works. Penguin give creative resources to the project, but they're not interested in it being a thinly veiled advertorial, or even, to be honest, a thickly veiled advertorial.

I think they're a great, great company in the way they're working with us. They understand that the gesture of doing this magazine is in itself the powerful part of the project. It's not about constantly mentioning Penguin. It's more having the Penguin logo on the magazine.

The front cover designs in particular relate to the visual history of Penguin, the original Penguin paperback covers.

They definitely immerse themselves in those graphics. Those two vertical lines, that have appeared on that cover occasionally, definitely reference that.

Helios Capdevila, who worked at that time on The Gentlewoman's design, was heavily involved as well. The idea was to give a sense of Penguin, to bring that atmosphere to the design without totally mimicking it. It really does feel to me like the love child of Penguin's design history and Fantastic Man's design history. You can’t quite put your finger on why, but it’s definitely there.

Do Penguin see The Happy Reader as something which sits alongside Fantastic Man and other independent magazines? Do they want to be in the independent magazine market, or is that not relevant to them?

I think they really do want to be part of it. Independent magazines are one of the big success stories of the moment, and they’re really excited to be part of that. We all work together very closely. Our ambition is to make a publication that works as a magazine first and foremost, rather than merely a promotional item.

Even post-publication, they’ve never responded to some part of it and said, ‘Could we have less of this?’

The only thing I’ve ever heard them feel slightly pensive about was when we mentioned someone whose book is published by Penguin, and they were worried that it would seem too much like they were plugging it. We've had Alan Cumming as our cover star, and his book’s published by Canongate. But I don’t want to be disingenuous. The Book of the Season is always a Penguin Classic. I don't think anyone feels that that's particularly problematic, because the that’s the greatest list of books in the world.

Do Penguin give you free rein to dig through their list and come up with something which relates to the season or a theme?

Yeah, I’m given free reign to do that, and then I send a list around to an editorial board that consists of Gert and Jop and a couple of people from Penguin. The choice isn’t based on a commercial sensibility. It's more about what we feel is right editorially.

One of the key differences between it and a more traditional literary magazine is the cover star and interview you run.

We never have somebody on the cover who is primarily an author. We have had people who have written books, like Kim Gordon or Ethan Hawke, but they’re better known as for other things, for music, or acting.

They’re not people you’d see on the cover of The Gentlewoman or Fantastic Man necessarily, but clearly the same care and attention is paid to the selection of those people for your cover as those others.

I’ve occasionally competed with those titles for interviews. There is a cross pollination. Or sometimes Fantastic Man will tell me who they've been offered and pass the conversation over to The Happy Reader, or vice versa.

When it comes to the interview, I characterise our approach as similar to Fantastic Man/The Gentlewoman's Q&As, which are really fun, and quite free-wheeling, but then they always get under the skin of a person in a way that a more knocking-on-the-front-door style interview might not.

We’re somewhere between that and a Paris Review interview, which is quite a carefully structured and studied attempt to get to the bottom of someone's creative process, something you might see in an anthology in a few years. Or perhaps we are a literary version of ‘Desert Island Discs’. I suppose I see our interviews as situated somewhere between these three models.

That leads nicely onto the name of the magazine. Was The Happy Reader always going to be its title?

It was already decided. It's very much in Jop and Gert’s style. I didn’t even need to ask the question. It's a phrase, isn't it, "I'm a happy reader." It swims against the seriousness of so much literary publishing.

‘Happy’ is a lovely word isn’t it? But also the reader is the person and also the magazine. It’s a reader.

Exactly. The focus on reading and readers is something we try and talk about quite a lot. It's a magazine for readers rather than for people who in some way see themselves as literary insiders.

I want people who read The London Review of Books to also pick up The Happy Reader and enjoy it. I want it to be taken both seriously and playfully. It's sort of a double agent. It was a deliberate decision to make it only 64 pages, you can read it in two and a half hours.

It’s like when the paperback first appeared, which was a Penguin innovation. The idea then was giving reading to the masses, and there's an element in the formatting and design that takes on that Penguin visual language, but there’s also something in the physical language of it, it’s like a paperback version of a magazine.

That’s true. A lot of independent magazines are hefty things, printed on thick paper but we’re instead borrowing the slightly disposable feel of original paperbacks. Except, then, just like those heftier magazines it's become a kind of iconic object. People collect them.

Do you have any idea whether Happy Reader encourages people to buy the Book of the Season? I know that’s not its raison d’etre, but does it have that effect?

Some people do. There is a significant subsection of people who are going out and reading at least some of the books. Then, as with any book club, some people show up and haven't read it and just want to socialise. I’d hate for those people to feel like they shouldn't read the magazine.

You’ve done some reading sessions. Is there a longer term desire to do something more permanent on the actual book club front?

I’ve just done a book club here in Singapore, and I’ve done a couple of events at Shakespeare & Company in Paris. I would love there to be Happy Reader book clubs that I don't know about. In a way, my dream is to choose the Book of the Season and then, when you sit on the tube, for it to be a bit like it was when everybody was reading ‘The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo’. Everywhere you went you'd see at least one person reading it. Imagine that with a classic novel.

The artist James Bridle came up with the concept of the ‘Invisible book club’, the idea being that everyone would read the chosen book, and then you'd all meet up somewhere, except you wouldn’t be allowed to actually talk about the book. You’d all just share the fact of having its atmosphere still in your heads, and that would be enough. I’ve no idea if he ever actually gathered such a club but I always liked the idea. Sometimes I think that essentially that’s what The Happy Reader wants to be: a huge invisible — or maybe in our case it’s more semi-visible? — book club.