Good Sport #5

Australian title Good Sport is a different kind of sports magazine, setting aside stats and fans to concentrate on sport as a metaphor for broader human activities: creativity, education and growth. Its fifth issue is out this month.

Our sample from that issue is typical of Good Sport’s approach; using the writer’s experience of fantasy football as an opener for explaining sociologist Jean Baudrillard’s theory of simulacra.

‘Baudrillard’s 1981 book Simulacra and Simulation is the type of book that causes your forehead to scrunch up in concentration before even putting a dent in the first few pages,’ says Good Sport editor James Whiting, ‘but I knew there was an adaptation of this thinking that connected sport and sport culture, in all their contemporary advances.’

James’ colleague Ben Clement knew regular contributor Christian Nathler would be the perfect writer. ‘Christian has a knack for explaining things with the kinds of analogies and hooks that make these dense topics feel not so daunting.’

Over to Christian…

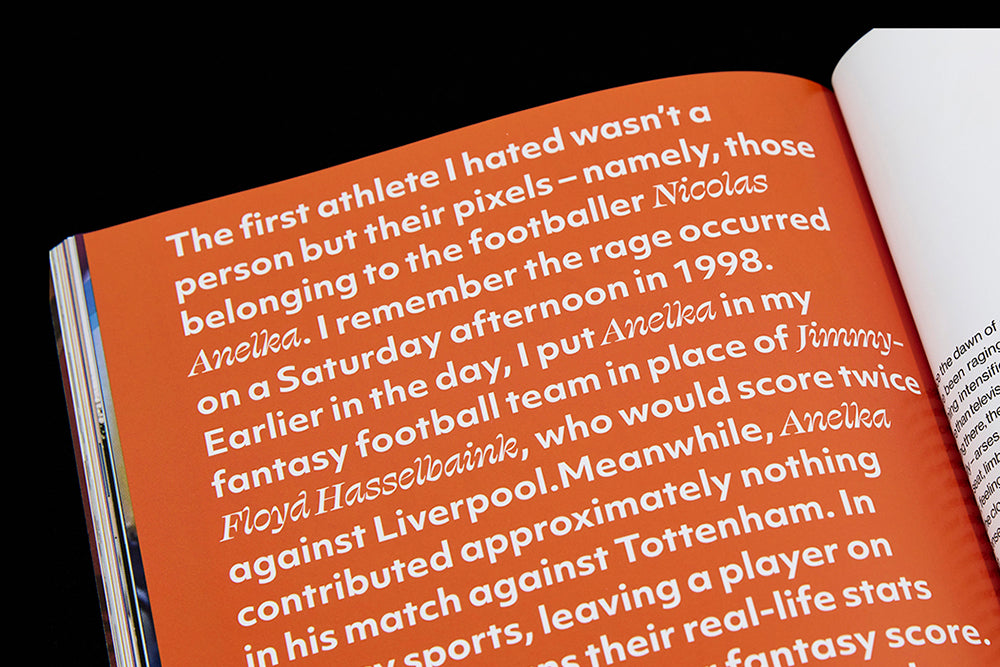

The first athlete I hated wasn’t a person but their pixels—namely, those belonging to the footballer Nicolas Anelka. I remember the rage occurred on a Saturday afternoon in 1998. Earlier in the day, I put Anelka in my fantasy football team in place of Jimmy-Floyd Hasselbaink, who would score twice against Liverpool. Meanwhile, Anelka contributed approximately nothing in his match against Tottenham. In fantasy sports, leaving a player on the bench means their real-life stats don’t contribute to your fantasy score. By not scoring, Anelka (vicariously through my poor decision-making) made real the fact that Hasselbaink’s goals, despite happening in real life (allegedly) on a football pitch in England, didn’t count in this life—the one on my screen and which mattered now and was, therefore, the more real of the two. I was nine years old. I wanted to smash my parents’ Dell.

Since the dawn of screens, men have been raging at them, and nothing intensifies this tradition more than televised sports. They’re sitting there, these men—hovering, really—arses grazing the edge of the seat, limbs akimbo and mouths ajar, feeling personally victimised by the closest they’ll ever come to a sense of injustice. I’ve often been that person, and it wasn’t until recently that I came to appreciate how enlightened it was for one girlfriend or another to see me in this state and tell me how dumb it was to get worked up about some-thing that isn’t real. It turns out much of modern life isn’t real.

That’s the layperson’s conclusion one might make (I made) after reading the French social theorist Jean Baudrillard. In his 1981 philosophical treatise Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard argues that most of reality has been replaced by signs of it: images, imitations, representations. Simulacra (plural). The colour blue as the look and taste of raspberries, for example. The power of simulacra is that they require no underlying truth for us to accept them as true. Raspberries aren’t blue and blue doesn’t have a taste, but that doesn’t matter to someone who’s never put one in their mouth.

When the signs combine and react to one another over time, they start to form a model of reality. Consider Instagram’s follower count as a sign within a model. A follower count, like all signs, relies on two things: a signifier (the number) and what it signifies (authority). Someone with many followers can exploit this relationship to create a whole system of signs. Say a popular fashion blogger uploads a photo of a green smoothie. What they’re doing is simulating health. The green colour of the smoothie is just one sign of it. Putting more kale in it doesn’t make it healthier, but Photo-shopping it greener does. The disruption of reality occurs in the meaninglessness of the ingredients.

‘Tropical’ and ‘berry’ at least resemble somewhat authentic flavours, but green? That’s a hell of a hyperreal drink. These days, the signs are so sly and ubiquitous that we can no longer distinguish reality from a simulation of it.

I know this sounds like stoner chat. I know you want to tell me that you’re not high enough for this. It’s early, it’s late, whatever. It’s a lot to take in; I get it. Be patient. Eventually, you’ll spot simulacra like a reflex. Ok, so there are all these simulacra. Some are simple, like memes, while others are deep, like identity.

I’ll never forget the TV commercial featuring NBA player Andrea Bargnani leaning on his Italian heritage to shill a pasta and sauce brand called Primo, which was owned by a Canadian food corporation called the Sunbrite Canning Ltd.

Let’s use Michael Jordan to level up the simulacrum. Bear with me for the sake of metaphor: Jordan didn’t just represent the sauce, he became the sauce. Michael Jordan the human became Jumpman the logo, which Nike turned into Air Jordan the basketball shoe. It’s like that meme about a trace of the true self existing in the false self, where the dinosaurs die and turn into oil that produces plastic dinosaur figurines eons later.

With the Air Jordans, it doesn’t matter that the real MJ effectively died two simulacra ago. All that matters is how you feel when you put his synthetic spawn on your feet. Baudrillard referred to this phenomenon as ‘sign value’—when an object’s perceived worth takes precedence over its actual worth. Sign value is an evolution of Karl Marx’s observation that, under capitalism, an object’s purpose (use-value) is less important than its relationship to other objects (exchange-value). ‘Will these shoes make me good at basketball?’ becomes, ‘Will these shoes make me better at basketball than other shoes?’ becomes, ‘Will these shoes make people think I’m the best at basketball?’ Combine that with the foolery of fashion and fuccboiism and it’s no wonder reality starts to fray.

Read the whole piece in Good Sport #5, out this week.

Team members: Ben Clement, James Whiting and Tim Leeson

Design: Griea Taylor, Jöelle Thomas