Mother Tongue #4

US magazine Mother Tongue quickly became an essential part of the indie scene when it first appeared a couple of years back, offering a vital, contemporary alternative to traditional parenting magazines.

Editors Natalia Rachlin and Melissa Goldstein described their magazine to us last year as being ‘Not. About. Kids.’ Which sums it up perfectly: it’s about mothers not children, mothers ‘who felt frustrated by the fact that their intellectual, professional, social, sexual, analytical lives were sort of overlooked once they were a mom…’

But like any good magazine, while that core subject is the glue that holds the whole thing together, there are plenty of stories that extend beyond the core. Stories like this latest ‘Close-up’ sample.

Natalia and Melissa explain…

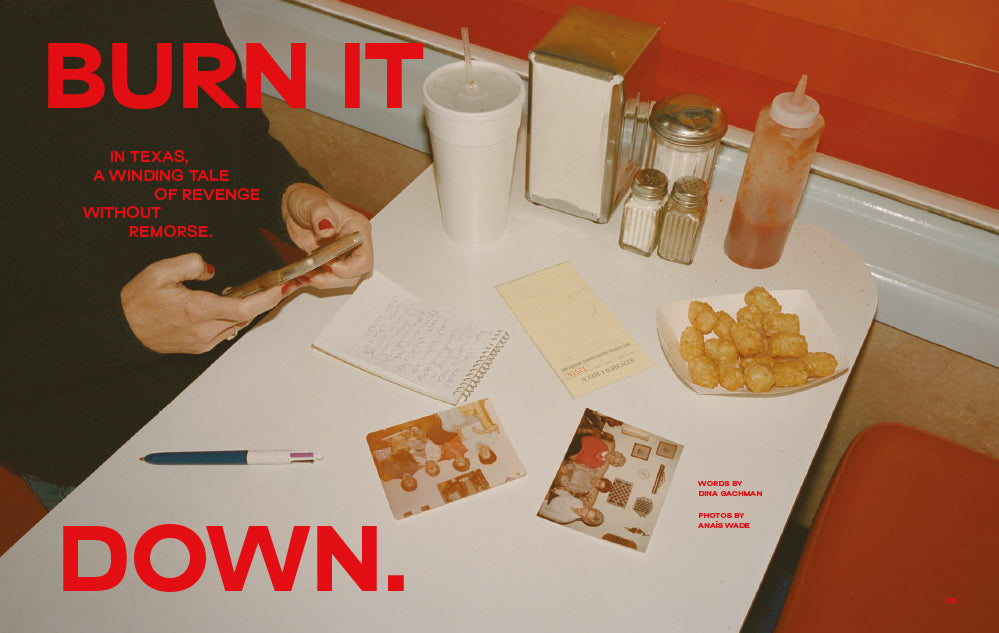

‘We’ve always loved the idea of incorporating juicy narrative journalism into the magazine—the kind of story that would “take you on a journey”—so when we were introduced to writer Dina Gachman through a friend, and she told us about a family secret she was keen to research further (involving a great aunt who may or may not have burned down the house of her abusive husband), we couldn’t say yes fast enough.

‘I have no idea if I’ll find anything,’ she warned us, ‘And I’ll need to go on a road trip to get answers.’ The words “road trip” sealed the deal. Fortuitously, one of our favorite L.A.-based photographers, Anaïs Wade, contacted us out of the blue to let us know that she had both air miles to spare and a thirst for a travel gig—considering the rigamarole with which shoots sometimes come together, it felt ridiculously easy?

‘We were thrilled with the results—both the engrossing story and the incredible imagery, but almost as good were the dispatches we got from the two of them on the road together. It reminded us why we feel so lucky to do this job in the first place: the privilege of meeting amazing women and being a catalyst for their stories.’

Over to Dina…

The North Texas State Hospital takes up 940 acres in Wichita Falls, a town about 140 miles northwest of Dallas. In 1922, the first patients—seven women sent from the county jail, whose crimes or behaviors society had deemed dangerous—entered the red-brick buildings of what was then called the Northwest Texas Insane Asylum. It was described as having a “parklike atmosphere” where “deranged persons” could tend gardens, milk cows and quiet their unsettled minds by knitting or picking carrots. The vast campus was intended to be a sort of oasis, where troubled citizens could stroll the grounds and heal in wide open space.

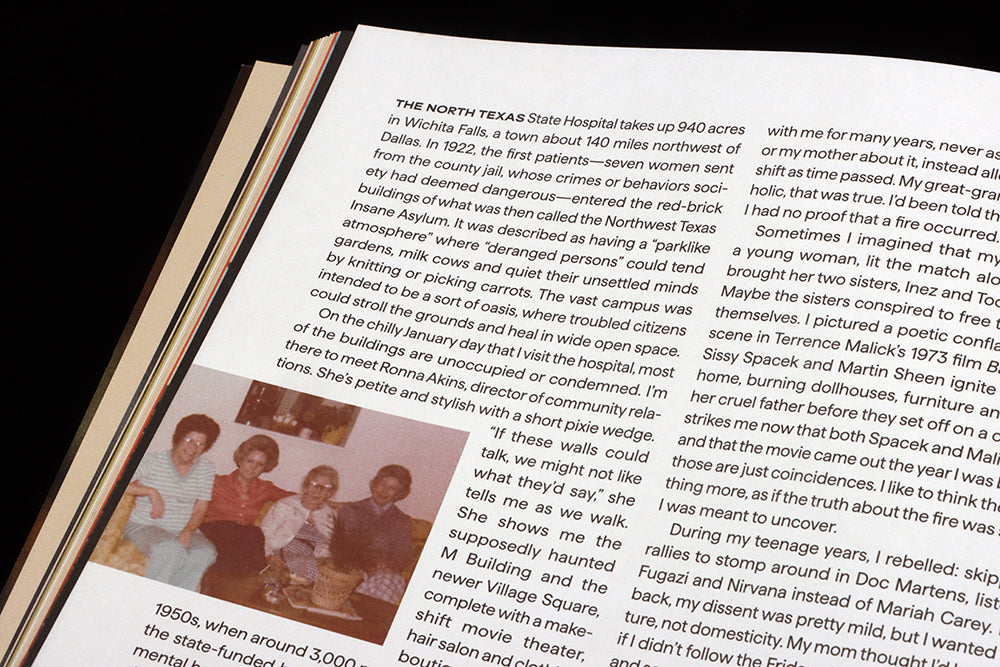

On the chilly January day that I visit the hospital, most of the buildings are unoccupied or condemned. I’m there to meet Ronna Akins, director of community relations. She’s petite and stylish with a short pixie wedge.“If these walls could talk, we might not like what they’d say,” she tells me as we walk. She shows me the supposedly haunted M Building and the newer Village Square, complete with a make- shift movie theater, hair salon and clothing boutique. Unlike the 1950s, when around 3,000 people filled the buildings, the state-funded hospital now houses less than 200 mental health patients. They don’t use the old electric shock simulator that sits on display in the lobby of the administration building, since treatments have thank-fully advanced over the last 100 years. They likely used that type of machine in the 1940s, though, the decade that lured me to this place in search of answers.

Back in high school, long before I knew that the state hospital existed, I was told the story of a fire. Like so many family legends heard too soon, facts faded and my teenage imagination took over, convincing me that my maternal grandmother, Eddie Faye, born in 1927, burned her family home down when she was young because her father was abusive. I carried this legend with me for many years, never asking my grandmother or my mother about it, instead allowing it to bloom and shift as time passed.

My great-grandfather was an alcoholic, that was true. I’d been told that he was rough, but I had no proof that a fire occurred. Sometimes I imagined that my grandmother, as a young woman, lit the match alone. Other times I brought her two sisters, Inez and Tootsie, into the tale. Maybe the sisters conspired to free their mother and themselves. I pictured a poetic conflagration, like the scene in Terrence Malick’s 1973 film Badlands, where Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen ignite her childhood home, burning dollhouses, furniture and the body of her cruel father before they set off on a crime spree. It strikes me now that both Spacek and Malick are Texan, and that the movie came out the year I was born.

Maybe those are just coincidences. I like to think they’re something more, as if the truth about the fire was something I was meant to uncover.

Editors Melissa Goldstein and Natalia Rachlin

Creative director Vanessa Saba