The Happy Reader #17

The Happy Reader continues it charming celebration of books and reading with a new issue, split into its two familiar sections. It opens with a longform interview—with artist Mark Leckey—and ends with a written examination of a single novel—this time ‘Middlemarch’.

That simple structure is the key its success. The Q&A with Leckey is a strong interview given the space to build a story culminating in his favourite books, against which the eight stories concerning ‘Middlemarch’ offer a more tangential, disparate patchwork of ideas spinning off from George Eliot’s novel.

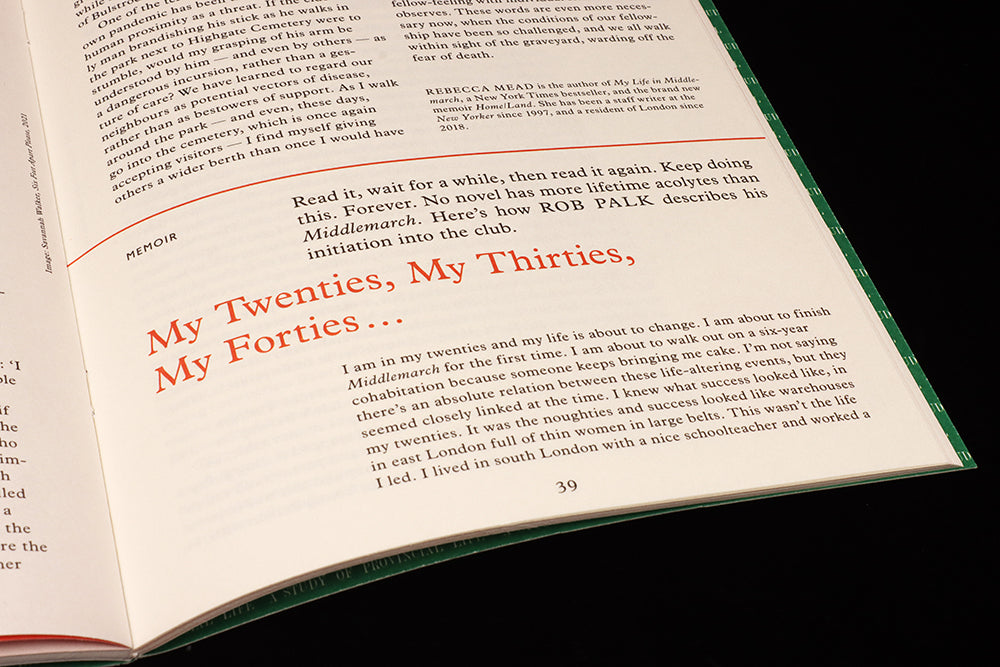

Our latest Close-up sample comes from the ‘Middlemarch’ section of the issue. Novelist Rob Palk’s piece describes how he first came to read and then reguarly re-read the novel.

‘Sometimes finding the right writer takes days or weeks,’ Happy Reader editor-in-chief Seb Emina told us, ‘It can involve tons of careful research. In this case it was more, oh, this person is tweeting a lot about his love for George Eliot’s novel ‘Middlemarch’, which is the theme of the next issue. I wonder if he'd be interested in writing something?

‘Happily, he was. Then it was me who didn’t reply for ages. I think I had an OK excuse though, given how my daughter had just been born, and earlier than anticipated. Anyway, the memoiristic essay he came back with did not disappoint. It’s a funny, poignant piece that I think could convince almost anyone to read Eliot’s colossal book’.

Over to Rob…

I am in my twenties and my life is about to change. I am about to finish Middlemarch for the first time. I am about to walk out on a six-year cohabitation because someone keeps bringing me cake. I’m not saying there’s an absolute relation between these life-altering events, but they seemed closely linked at the time. I knew what success looked like, in my twenties. It was the noughties and success looked like warehouses in east London full of thin women in large belts. This wasn’t the life I led. I lived in south London with a nice schoolteacher and worked a boring job. Only someone at this job kept bringing me cake.

The cake-bringer worked in the same large charity office as me, in the room next door to mine. Three or four times a day she brought me offerings: cups of tea, wedges of lemon drizzle, occasionally books. When she brought the tea, she stood above me and we talked. Silence rippled out along the workspace. People pretended, not very skilfully, to be occupied. The cake-bringer’s skin turned a pinker colour. The cake-bringer wore a heavy perfume and, when I drank from the cup she had brought me, her scent lingered in my hands. She was friends with people in bands. She had ‘done’ some modelling! She often went to Berlin. She was the success world made flesh. I wanted this. She was reading Middlemarch and so I read it too.

I know: I should have read it before. I thought of it as the sort of book my sister liked: fat, with a black spine, all big houses and governesses and crinoline and squabbles over inheritances. Books I liked were thin, with blue-green spines, and featured chain-smoking men having melancholy affairs in hotel rooms with drunk women called Yvonne. I also knew that Middlemarch was supposed, in a vague way, to make you a Better Person, like vitamins or yoga or going to Bali. I didn’t want to be a better person and maybe this put me off.

The first thing the book brought: a deep immersion, the sort you normally lose in adult life. I was there in Tipton Grange, I could smell the stables and the dust on the jewellery boxes, hear the papery swish of dresses in motion. The next step was feeling, as we didn’t say in the noughties, seen. More than any other author, George Eliot seemed able to lift the lids of our heads and take a look around. This had a quelling effect. Somehow this author knew everything. No vanity escaped her. She knew what it was to be young and ardent and have no outlet. She knew what it was to let your better urges get hobbled by weakness. She knew what it was to be a sceptical but conscientious vicar or a guilty Methodist banker, a husband who marries an idea. She would pop up every few pages or so and tell us what to think, and somehow this wasn’t annoying but the best part of the book. She knew about men. Boy, did she know about men. She knew about failure. There were so many ways to fail. You could come a cropper in middle age for the crimes committed in youth. You could be reckless or unwise in love. You could fail to speak out on minor injustices, fail to challenge prejudices or challenge the wrong ones. You could let ‘spots of commonness’ override your better plans. You could drift from arty dabbling to worthwhile cause and back again, never finding your path. You could be Casaubon. This was the scariest fate, a character seemingly made up of homilies and old parchment until, in one of the great record scratches in literature, Eliot stops the action and shows his soul, shows us someone we could be, if we buried ourselves in futile projects, if we let our fear of failure confirm us in our failing.

Read the whole of Rob Palk’s essay in the latest issue of The Happy Reader.

Editor-in-chief: Seb Emina

Art director: Tom Etherington

Editorial directors: Jop van Bennekom & Gert Jonkers